Planet Formation Witnesses and Probes: Transition Disks

DFG Research Unit: FOR 2634/1, 2634/2

Planet Formation Witnesses and Probes: TRANSITION DISKS

DFG Research Unit FOR 2634/1

Recent surveys have shown an overwhelming diversity of extrasolar planetary systems, prompting the question of how did they form, and whether some may end up looking like our own and being able to sustain life. Hints to answer such fundamental questions may be hidden in the many trends that are slowly emerging from the data. An example are the deserts and peaks in the distribution of giant exoplanets, with clear implications for habitabil- ity of systems, given the role played by giants on the delivery of volatiles to terrestrial planets (e.g., Quintana & Lissauer 2014).

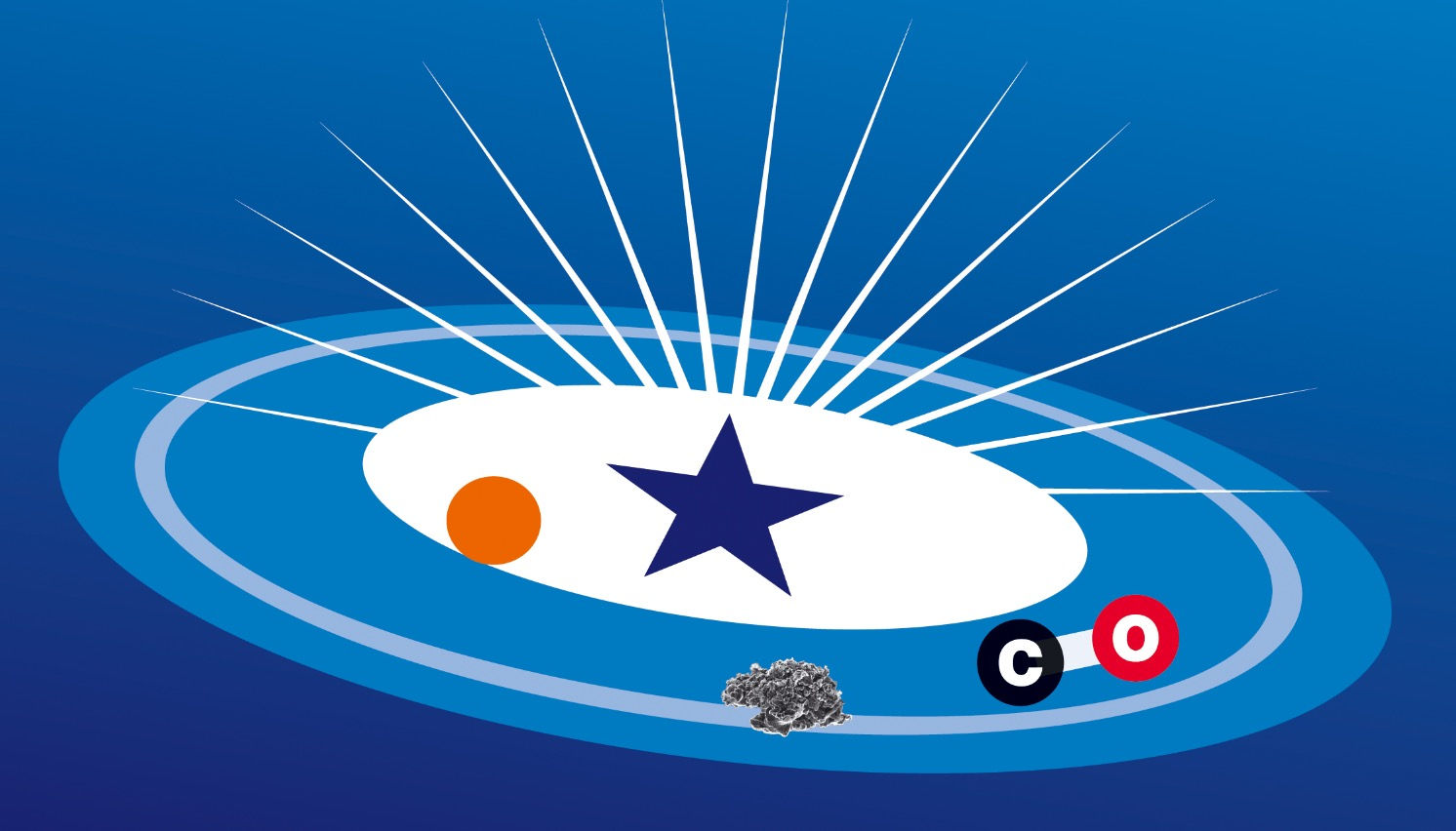

The environment in which planets form plays a major role in understanding both the variety of exoplanets and the emerging trends. Planets are born out of the dust and gas left over whenever a new star forms: the protoplanetary disk. The initial conditions for planet form- ation are thus determined by the protoplanetary disks, which evolve and disperse as they give birth to planets. Interestingly, the timescales of disk dispersal are comparable to those of planet formation, suggesting that the dispersal mechanism dominates disk evolution right at the time at which planets form. Conversely, the planet formation process also strongly af- fects the disk, making the combined problem of planet formation and disk evolution a strongly coupled and complex problem.

Disks on the verge of dispersal, so-called “Transition Disks” (TDs), are thus particularly important witnesses of the planet formation process, and they can be used as probes of the different mechanisms at play at this crucial time of disk evolution. Latest research has shown, however, that TDs, which are usually identified as disks showing evidence of an (at least partially) evacuated inner dust hole, are in reality a diverse class of objects. Some TDs have relatively small dust holes (a few AUs) and are weakly accreting, if at all. On the other hand an apparently distinct population of TDs show evidence for much larger inner dust cavities (several to many tens of AU) and vigorous accretion, signifying that a large amount of gas is present inside the dust cavity. Different physical processes may be at play for the forma- tion of different TD types (e.g. photoevaporation, MHD processes, dust evolution, planet-disk interactions), each being a piece of the complex planet formation puzzle.

Until recently, observations of protoplanetary disks provided very few constraints on our un- derstanding of disk evolution and planet formation. That was in part due to the lack of spatial resolution of telescope facilities at infrared and (sub-)millimetre wavelengths, but also in part because protoplanetary disks tend to be opaque, and therefore much of the planet forma- tion process is hidden from view. Both these obstacles impede an unobstructed view of the physical processes happening inside these planetary nurseries. Both problems may now start to be overcome with the enormous recent advances in the observational facilities. At near infrared wavelengths and at millimetre wavelengths we now start to obtain extraordinar- ily detailed images of these disks. They turn out to feature complex (often non-axisymmetric) structures that challenge our theoretical understanding of these disks. In particular, many TDs show spectacular structures including lopsided blobs, rings, spirals etc. It is suspected that some of these complex structures may be caused by newly formed giant planets that gravitationally perturb the disk, but exciting new alternative explanations, which not always involve planets are also emerging.

In our Research Unit we aim at studying various aspects of TDs, leading to a bet- ter understanding of the different formation mechanisms of this very diverse class of objects. TDs are only now really becoming spatially resolvable thanks to facilities like ALMA and VLT- SPHERE, making their study a timely and urgent task. Only understanding the disk evolution and the planet-disk interactions allow the large body of existing and planned observations to be exploited to answer more complex questions like the formation of planetary systems capable to host life. This requires a focussed effort from several communities to devise a multi-pronged strategy to approach to tackle the problem. Specifically, multiwavelength observations of disks at different stages of evolution together with exoplanet and disk statistics should be used to constrain a concerted theoretical modelling effort including the hydro- dynamics of the dust and gas component of disks, with and without planets, joint to chemical and radiative transfer calculations, particularly of the surface layers and winds of disks in (or just before) the transition phase. This is the motivation for the Research Unit.